The AMD Athlon, also known as the AMD K7, came charging onto the scene in the summer of 1999, thoroughly wrecking Intel’s fun. In February, Intel launched the Pentium III, a supercharged upgrade of the P6 microarchitecture. Cyrix was effectively finished, its tech now in the hands of VIA Technologies.

That just left AMD, whose K6 processors had captured some of the budget PC market, but didn’t have the optimized pipelines, cache, or floating point performance to give Intel any serious competition. Then the Athlon changed everything.

When AMD released its first K7 Athlon processors to reviewers in June, something unexpected happened. Sure, there was already some buzz about the new CPU, thanks to intriguing early demos and briefings, but a Pentium III killer? Not likely. Yet when the final production samples hit magazine labs and website test benches, it became clear that the new Athlon was pretty special.

AMD’s chip wasn’t just matching Pentium III, clock speed for clock speed, but beating it. Worse, it was beating it in the kind of floating point-intensive apps that Intel considered home territory, including 3D games. Athlon was kicking Intel right where it hurt, and that eye-watering discomfort wasn’t going to let up any time soon.

AMD Athlon architecture

How exactly did AMD manage this feat? Well, as with so many standout products in the hardware space, the answer involves several developments all coming together at the same time. On the one hand, the success of the K6 II and III had left AMD in a surprisingly strong position.

The K6 architecture had made the most of technology bought in with the company’s 1996 acquisition of NexGen and had pumped money into AMD’s war chest. It had also cemented AMD’s position as Intel’s most credible rival.

What’s more, AMD also had new CPU and bus technology developed by the Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) for its Alpha RISC processors. It had even taken on most of DEC’s RISC CPU design team, including key architects, Dirk Meyer and Jim Keller.

Thanks to a patent cross-licensing deal with Motorola, AMD also had a head start on new copper-based die manufacturing technologies, not to mention a new chip fab in Dresden on its way to use them. This would become important later on.

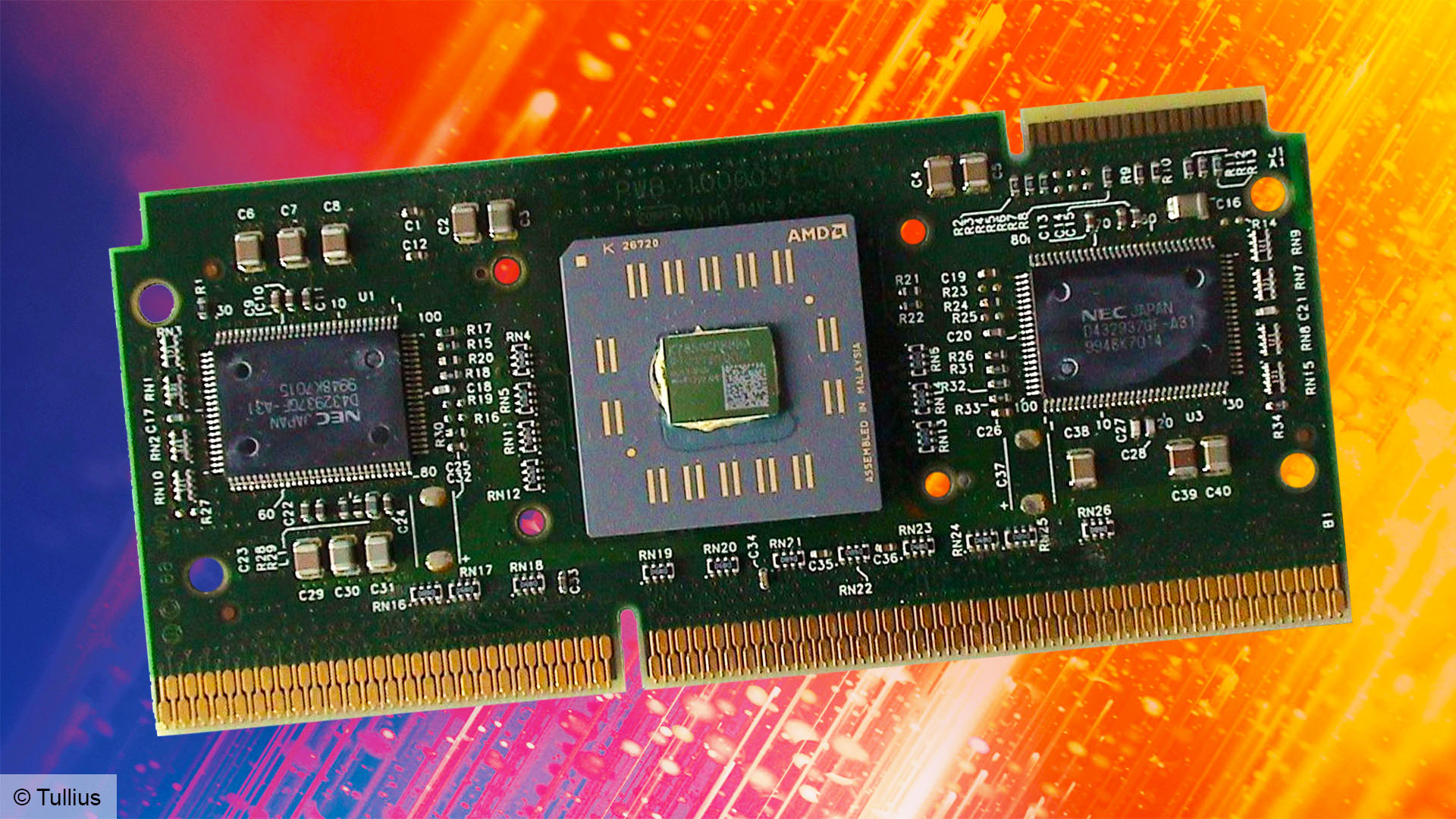

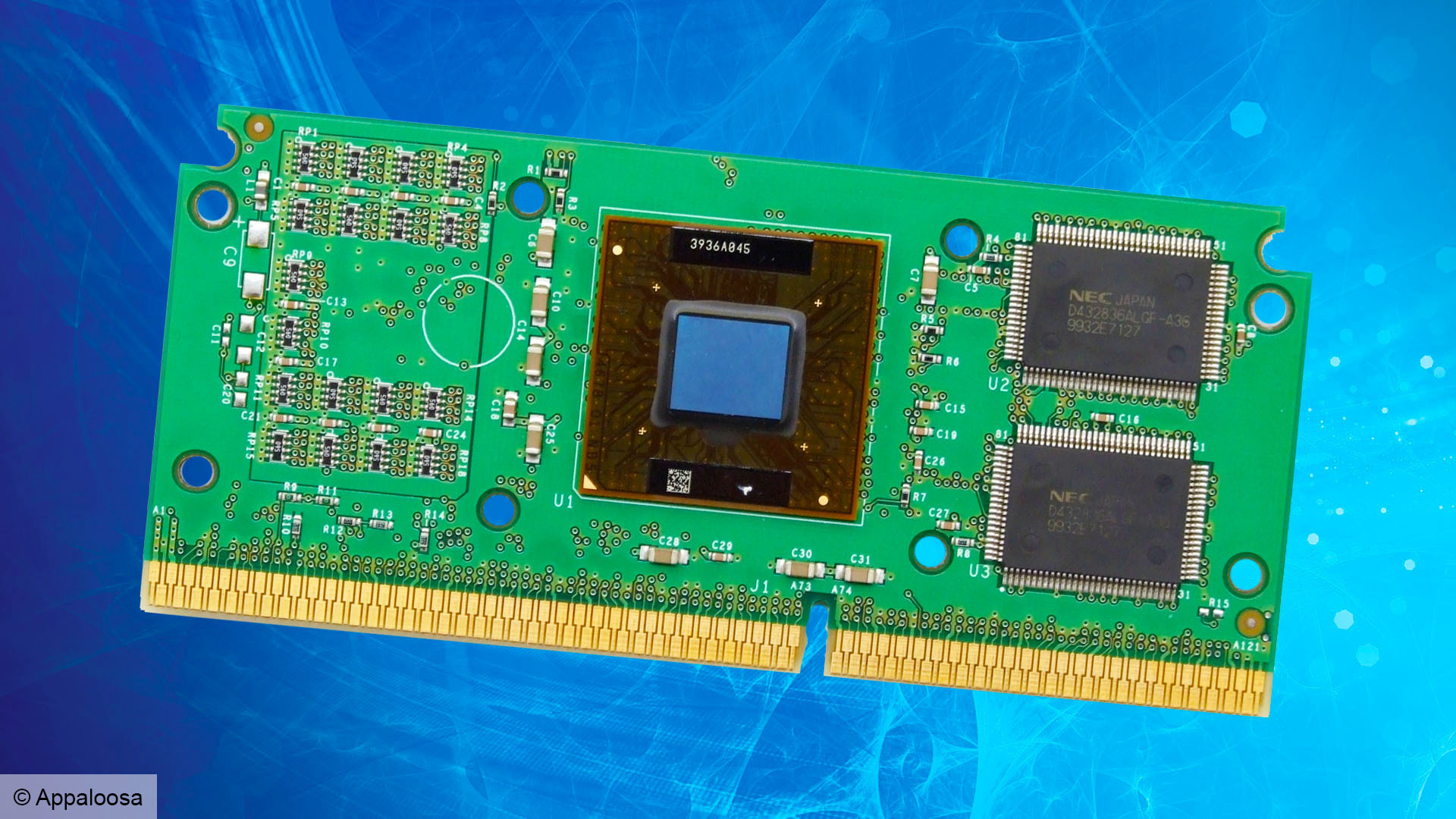

All this helped lead to a revolutionary design – the first 7th-generation x86 processor. The original 0.25-micron (250nm) Athlon had a die with over 22 million transistors – the highest transistor count of any x86 processor to date. It also had an ingenious split cache system, with 128KB of on-chip L1 cache operating at clock speed, plus another 512KB of L2 cache included in the processor module.

This L2 cache operated at a fraction of the clock speed – half-speed on the initial models – but with breathing room to scale to cover higher and slower speeds later on. This arrangement gave Athlon a performance advantage over the earlier K6 processors, even before you factored any other architectural improvements into the equation.

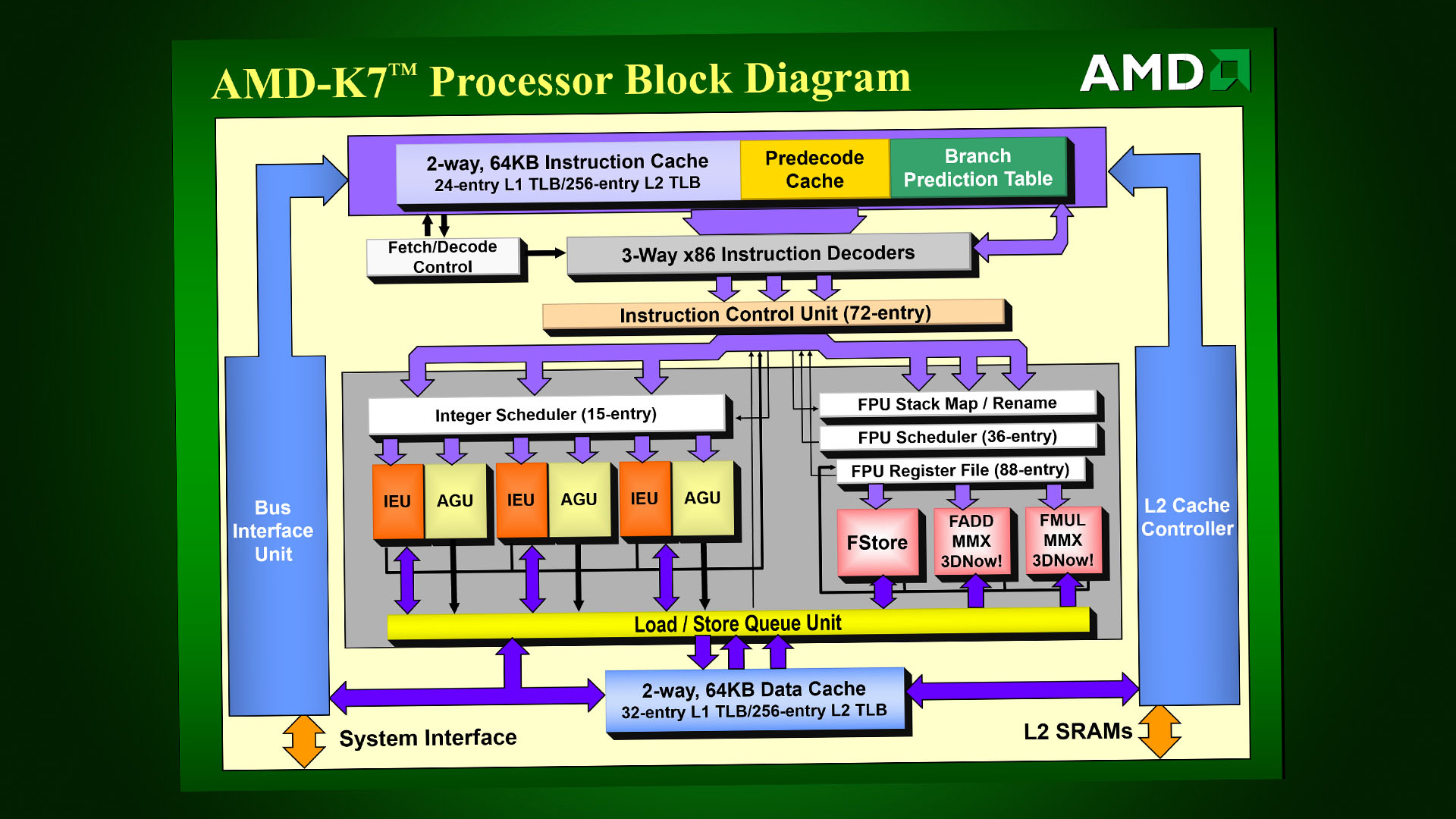

But these improvements were just as significant. Meyer, Keller, and their team designed an architecture that was capable of decoding three x86 instructions simultaneously and – crucially – symmetrically, unlike the Pentium III.

True, the Pentium III’s instruction pipeline could handle three simple instructions at once, but feed it more than one lengthy, complex instruction and it choked, as only one pipeline could manage the workload. The Athlon, by contrast, could chew through three complex instructions without any trouble. You got three instructions at a time, every time.

What’s more, the design featured a new level of optimized branch prediction, which was not only more accurate in guessing what the next operation would be, but faster to recover when it got that guess wrong.

Like the team brought in from NexGen, the team brought in from DEC had serious skills and experience in RISC chip design, and AMD put this to good use. The Athlon architecture converted x86 instructions into more efficient ‘macro ops’ and then those ‘MOPS’ into RISC operations, which the CPU’s execution units could work on, nine to a clock.

This design was incredibly efficient by the standards of the day, but it was also conducive to scaling upwards. Where the K6-III had been stuck at 500MHz, the Athlon launched at 500, 550 and 600MHz speeds, matching the 600MHz of Intel’s top-end Pentium III. As if that wasn’t enough, AMD added a 650MHz version in fewer than six weeks after launch. The final kicker was that AMD was no longer second rate on floating point operations.

Not only were the Athlon’s floating point units (FPUs) much faster than the weedy FPUs of the K6 line, but AMD built on the SIMD instructions of its 3DNow! Technology, with 24 new instructions on top of the original 21. Most mimicked the cache and streaming controls seen in Intel’s mighty SSE tech, but AMD also bundled in new DSP and complex maths extensions, plus MP3 and Dolby Digital decoding tools. This chip was built to game and entertain.

There was one final way that AMD now matched Intel – the Athlon was AMD’s first chip to abandon sockets and embrace the slot. AMD’s Slot-A connector harnessed DEC’s EV6 bus and bus protocol, which allowed for burst data transfers at double the rate of Intel’s equivalent GTL+, giving you a whopping 1.6GB/sec of bandwidth between the CPU and the motherboard chipset.

The Athlon’s front side bus operated at double the 100MHz speed of the memory bus, and as faster RAM became available, this gave AMD scope to up the FSB speed even further, to 266MHz or even 400MHz. What’s more, with a slot design, AMD could combine its CPU die and L2 cache in the one package, and that package was a whole lot easier to fit. And to make sure dozy upgraders didn’t try to stuff AMD CPUs into Intel slots or vice versa, it cleverly reversed the physical design.

AMD Athlon benchmarks

Talk about architectures and specs was all very well, of course, but nothing really prepared those of us benchmarking PCs in the late 1990s for the sheer undeniable awesomeness of Athlon. The results of benchmarks wouldn’t have made comfortable reading for Intel, especially once the Athlon 650 rolled out in August. Both the Athlon 600 and Athlon 650 were faster than the Pentium III 600 in Quake III: Arena, whether paired with the hero graphics chip of the day – the Nvidia Riva TNT 2 – or with the still speedy 3dfx Voodoo 3.

The Athlon was around 10 percent faster in standard Windows applications, and up to 20 percent faster in gaming benchmarks. The Athlon 600 was 10fps faster than the Pentium III 600 in the fiendishly demanding Quake II Crusher benchmark. As further tests from the likes of AnandTech proved, even a Pentium III overclocked to 650MHz couldn’t keep up.

And this was just the beginning. In September, Intel launched the Pentium III 600B – a variant of the ‘Katmai’ Pentium III with a 133MHz front side bus (pictured below). It couldn’t match the Athlon 550 in many benchmarks, let alone the 600 and 650MHz versions, and still lagged behind the Athlon in when it came to gaming performance.

In October, AMD responded with a 700MHz Athlon that pulled even further ahead. AnandTech’s benchmarks of the time put it 20 percent faster than the Pentium III 600B in the Quake II Crusher benchmark. It was nearly 27 percent ahead in Quake III.

It was only with the launch of its Coppermine Pentium III processors in October 1999 that Intel could claw back the lead. Yet while the Pentium III 733EB was now king of the hill, an Athlon 700 could still benchmark faster in many tests than Intel’s 700MHz Coppermine Pentium III.

As the clock speeds rose, the competition just grew hotter. In November 1999, AMD launched a new series of Athlons with a 0.18-micron (180nm) K75 core, taking the top speed up to 750MHz. In January and February, these were followed with 800 and 850MHz CPUs. Then just as Intel geared up to launch a (gasp!) 1GHz Coppermine Pentium III in March 2000, AMD stole its thunder by launching the Athlon 1000. To really take the proverbial, it did it two days earlier, giving AMD the first 1000MHz x86 CPU.

Athlon was first, but it wasn’t the fastest. The Pentium III 1000EB was actually ahead of the Athlon 1000 in many tests, partly due to superior SSE support in many popular benchmark games.

Yet there were only a few frames per second in it, and Athlon systems often had the edge on price. What’s more, the Pentium III 1000 was only available to system builders at the time of launch. Anyone could get their hands on the 1GHz Athlon at the time.

AMD Athlon compatibility issues

Of course, no new CPU comes without teething troubles. Early buyers found a range of compatibility issues with specific hardware, partly because Athlon was a complex, power-hungry CPU, and partly because of AGP slot power issues affecting many motherboards and driver issues with the latest Nvidia cards.

With certain VIA chipsets and less consistent power supplies, you could find yourself in a world of instability. Nvidia even released a driver update for its graphics chips that disabled the high-performance 2x mode on the AGP slot when Athlon was detected.

AMD Athlon overclocking

Some enthusiasts were also disappointed with the Athlon’s limited overclocking potential. The K6 line had been a treat for overclockers – gamers upped 450MHz CPUs to 600MHz routinely, and there was much debate in PC magazines about whether we should allow manufacturers to send in pre-overclocked systems.

The Athlon wasn’t having any of that. The only ways to overclock the original CPUs were to crack open the modules and interfere manually with the resistors, or to purchase a third-party ‘Goldfingers’ device which did it all for you. Through either method you could increase your multiplier and give your Athlon a healthy speed boost, although it meant invalidating your warranty along the way.

AMD Zen Athlon

The Athlon set the stage for a golden age of PC CPUs. Intel struck back with Coppermine, then AMD replaced the K7’s old aluminum interconnects with copper, and ran the L2 cache at the full speed of the CPU. The 2nd-generation Athlon ‘Thunderbird’ processors could match and even beat the Coppermine Intel Pentium IIIs, causing Intel to push even further with its Coppermine T CPUs.

Before we knew it, 1GHz was starting to look like old hat – 1333MHz and 1400MHz were the new targets. Meanwhile, the K7 architecture was making waves at the budget end. Where Intel’s cheap, cache-less Celeron processors couldn’t handle Deus Ex, Half-Life, or Unreal Tournament, AMD’s K7 Duron CPUs were storming through them.

There’s still a lot of affection for the Athlon in the PC enthusiast community. At a time when Intel seemed unassailable, it was the first chip to really knock it off its feet. This made Intel try a little harder, and the result was that everybody won. In fact, it’s a mark of that affection that when AMD created a new budget Zen-based processor line-up in 2018, it still used the Athlon brand, with the Athlon 3000G coming out in November 2019. It’s a sign of a classic brand when it’s still being used 20 years later.

Naturally, we’re no longer using K7 CPUs in slot format but processors based on the new AMD Zen 4 architecture have really impressed us. If you’re looking to buy a new processor, take a look at our guide to the best gaming CPU, where we take you through all the best options at whatever your budget. One of our favorites from AMD’s current chip lineup is the AMD Ryzen 7 7800X3D, which has amazing gaming performance.

We hope you’ve had as good time reading this retrospective about early AMD CPUs. For more articles about the PC’s vintage history, check out our Retro tech page, as well as our full guide on how to build a retro gaming PC.