In March 1998, Nvidia launched a product that punched a hole in the 3D graphics map, the Nvidia Riva TNT. It’s hard to imagine, but at this point, Team Green was very much a secondary player. 3dfx ruled the sector with its mighty 3dfx Voodoo2 – the dedicated 3D graphics card every PC gamer wanted.

The Voodoo2 offered a vastly higher level of performance than the integrated 2D/3D chipsets of the time, including the ATI 3D Rage Pro and the Nvidia Riva 128. There was some hype around Nvidia’s next 2D/3D chipset, codenamed NV4, but arguably more around ATi’s upcoming 3D Rage 128 and S3’s Savage 3D. As a tech journalist at the time, I’ll tell you frankly – we weren’t prepared for what NV4 would do.

Admittedly, the NV3 chip in the Riva 128 should have given us some idea. With 3.5 million transistors, a 100MHz core clock speed and support for Intel’s new Accelerated Graphics Port (AGP), it was one of the first 2D/3D chipsets fast enough to slug it out with the original 3dfx Voodoo Graphics cards.

However, dodgy drivers and odd choices when it came to mipmapping and texture filtering – both key to making PC games look good – meant that image quality wasn’t where it should have been. It was another contender, nothing more.

This made the debut of NV4 as the Riva TNT all the more shocking. Here was a chip that could go toe-to-toe with the Voodoo2. What’s more, in early briefings, Nvidia claimed it would hit the same performance levels as two Voodoo 2 cards in an SLI configuration.

On top of that, it would be able to run games at resolutions of up to 1,600 x 1,200, where a single-card Voodoo2 stopped at 800 x 600, while an SLI setup was limited to 1,024 x 768. Just as crucially, Nvidia’s image quality problems were over. Some even believed the TNT’s render quality was superior to 3dfx’s best.

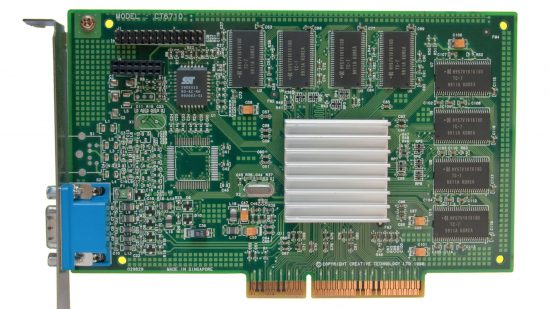

Nvidia partnered up with the likes of Creative (pictured), STB, Hercules and Diamond to deliver cards based on its chip. Photo credit: Own work by Tors, Public Domain

Twin texel action

So how did Nvidia pull this off? The secret ingredient is actually hidden in the product name, with TNT standing for TwiN Texel. Where rival 2D/3D chips had a single rendering pipeline, the TNT had two, operating in parallel to produce one pixel per clock cycle.

This effectively doubled the pixel fill rate – the number of pixels the card could render to the screen every second – and did much the same to overall performance. It was a feat that, at this point in time, only 3dfx had managed.

Nvidia’s timing here was nearly perfect. At this point in the development of 3D graphics, game engines and APIs were growing more sophisticated. With 1st-generation products, such as 3dfx’s Voodoo Graphics or the Rendition Verite V1000, it was enough to render fairly simple polygon scenes with bilinear filtered textures and Gouraud shading – the hallmark of realistic 3D graphics of the time.

By 1998, however, programmers were implementing techniques such as bump mapping and multi-texturing, allowing new lighting, shadow and depth effects to be used in games.

By doubling up on the Riva 128’s technology with its Twin Texel engine, the TNT redefined what a single 2D/3D chip could do. Photo credit: Own work by Hyins, Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 2.5

Crucially, these same features were supported in DirectX 6 – the next version of the API and the first to get real traction with most game developers – along with OpenGL, as used in id Software’s Quake II and the soon-to-be-released Unreal.

With a single texture pipeline, most graphics chips had to process these effects in two passes, slowing down frame rates at a time when sub-30fps frame rates were the norm for many PC gamers. In 1998, every last frame counted.

The Voodoo2 had a real advantage here, with two pipelines through which to accelerate these new effects, while the Riva 128 – like all other 2D/3D graphics chips then – had just the one. As a result, while earlier 3D titles flew on Nvidia’s chip, newer games with multi-texturing effects were a different story.

The 3dfx Voodoo2 dominated 3D graphics like no other card before or since. Before the TNT, no 2D/3D card could rival it

The Riva TNT was the first graphics chip produced outside 3dfx that could handle these operations in a single pass. What’s more, it supported higher-resolution textures and trilinear texture filtering, enhancing visual quality.

Nor had Nvidia neglected key upwards elsewhere. It had already moved to the faster AGP 2x speed with the ZX spin of the Riva 128, doubling bandwidth over the bus from 266MB/sec to 533MB/sec. What’s more, it had shifted from the EDO DRAM of previous graphics cards – the same EDO still being used in the Voodoo 2 – to much faster SDRAM. Plus, where the Riva 128 had been limited to 4MB and the Riva 128ZX to 8MB, the Riva TNT had a glorious 16MB, clocked up from 100MHz to 110MHz.

The TNT also supported 32-bit color at a point where many graphics chips were limited to 16-bit. This wasn’t a big deal, given that most game engines couldn’t handle any more than 64,000 on-screen colors, but it gave the TNT in a degree of futureproofing as more advanced titles came out.

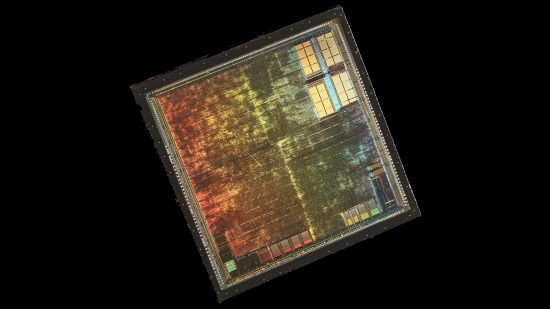

With 8 million transistors in a 128mm² die, the Riva TNT pushed 0.35-micron technology hard. Running at 120MHz was a step too far. Photo credit: Own work by Fritz Fritzchens, Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 1.0

Proof of performance

When Nvidia announced the Riva TNT at the WINHEC conference in March 1998, it pushed out some pretty big numbers. Cards would be capable of a 250 megatexels per second fill rate, and an 8 million triangle per second polygon throughput, at a time when most 2D/3D chips were struggling to reach 100 megatexels per second and 2 million triangles. Nvidia claimed that early performance tests showed results that competed directly with two Voodoo 2 cards in SLI.

Sadly, this didn’t translate to the finished product, as Nvidia’s new chip struggled with overheating. The Riva TNT was designed to run at 125MHz, but it was a massive chip with 8 million transistors, pushing the limits of the 0.35-micron technology of the time.

At 125MHz, the chip ran too hot to be reliable, particularly when most graphics cards relied on passive cooling. As a result, Nvidia clocked the final Riva TNT down to 90MHz, with a corresponding loss of performance. The single chip built to thrash the Voodoo 2 was now ‘only’ on a par.

Did this matter? A little, but not much. In 1998, a Voodoo2 was still expensive, and you needed a separate 2D graphics card to handle every job outside 3D games. Whereas the Voodoo2 on its own would set you back around £200, you could find a Riva TNT card for slightly less money, and it was the only graphics card you needed. What’s more, the early benchmarks told their own tale.

One of the most cutting-edge games of 1998, Forsaken used a range of new DirectX 6 effects. This screenshot is taken from the 2018 HD remaster

In Forsaken, one of the era’s big Direct X showcase games, Nvidia’s card was significantly faster than any of its 2D/3D rivals, and ahead of the Voodoo2 at both 640 x 480 and 800 x 600. It was a close match for the Voodoo2 in Turok: Dinosaur Hunter, it could beat it in Quake 2 at 800 x 600, and it wasn’t far behind in 640 x 480. We put it to the test in the lab and came away amazed; where even the most advanced 2D/3D chips slowed down and stuttered, this thing flew.

Game developers were equally impressed. Nvidia put out a press release around the ECTS game show in September, where superstar developer David Perry raved about the Riva TNT. With this card, his new game Messiah could run at 1,920 x 1,080 and still look good. Paul Finnegan of Rage Games, the team behind hot new title Incoming, said the Riva TNT had the DirectX 6 key features needed to deliver ‘a visual experience second to none’.

However, there were still two caveats to the Riva TNT’s performance – 3dfx still had the edge on many games that used its own proprietary Glide API, while its cleverly optimized MiniGL drivers sometimes gave it the edge in games based on OpenGL. As this included any game running on the Quake engine, and many of the era’s biggest blockbusters, this remained a thorn in the side of the Team Green challenger.

More seriously, Riva TNT was still dependent on the CPU to handle the initial triangle setup, whereas the Voodoo 2 handled that on-board. As a result, the Riva TNT was a monster on the fastest Intel Pentium MMX and Pentium II systems of the day and pretty good on the AMD K6. Give it the older AMD K5, a floating-point challenged Cyrix 686 or lower-end Celeron, however, and the CPU just couldn’t keep pace. On those machines, you were better off sticking with a Voodoo 2.

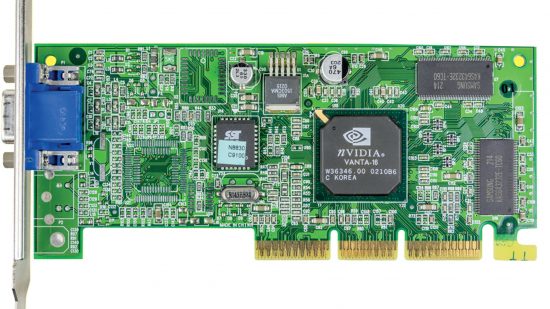

The Vanta was the first in a long line of cut-down Nvidia graphics chips. You might have found this one in a Compaq desktop PC. Photo credit: Own work by Raimond Spekking, Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 2.5

Nvidia Riva TNT Vanta

Nvidia also set a new standard for the graphics card industry by releasing a budget version of the TNT, dubbed Vanta. This was effectively the same chip running at a lower clock speed, with a 64-bit memory interface and half the amount of RAM as a standard TNT.

Designed to bring Nvidia’s graphics tech to business desktops, it also found its way into budget gaming systems, leading to some disappointment when it didn’t deliver the same levels of performance. Today, of course, using GPUs that don’t make the grade at their intended spec in a lower-end product is standard practice, and this wasn’t to be the last time that Nvidia released cut-down chips to expand into a cost-conscious market.

The Nvidia Riva TNT legacy

The launch of the Riva TNT had big implications for the future of the graphics card industry. It put paid to the idea that you needed a dedicated 3D card, and pushed both 3dfx and Videologic’s PowerVR team to focus on their own 2D/3D processors. Even then, Nvidia opened up a technology lead, with its successor TNT2 chip outperforming the 3dfx Voodoo3.

The TNT’s success also made it harder for existing graphics specialists to compete in an aggressive market. Rendition and S3 would soon abandon their own 2D/3D efforts, while Matrox largely retreated from the gaming market to focus on high-resolution, high-color chips for professional graphics and design. Only 3dfx and ATi would remain in the battle, the former eventually purchased by Nvidia, the latter by AMD.

The Riva TNT was also one of the first graphics processors that rewarded overclocking, as enthusiasts and some card manufacturers realized that a chip designed to run at 125Hz could still be pushed to 100MHz or over, particularly with some help from active cooling. The manufacturers released utilities with which you could push the core clocks and memory clocks upwards, and soon gamers were enjoying the free speed boost.

Most of all, the Riva TNT and its successor put Nvidia on the path it treads today: a leader in graphics, AI accelerators and even system-on-chips in certain markets. It would have other revolutionary products, such as the Nvidia GeForce 256 and the first RTX chips – but the TNT was where it all kicked off.

Moving to the present day, Nvidia is now a dominant name in PC gaming. If you’re looking to upgrade to the latest Nvidia or AMD GPU, make sure you read our full guide to the best graphics card, which covers the best options at a range of prices. You can read all about one of our current favorites from the firm that brought us the Riva TNT in our full Nvidia GeForce RTX 4060 Ti review.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this retrospective about the early days of Nvidia. For more articles about the PC’s vintage history, check out our Retro tech page.