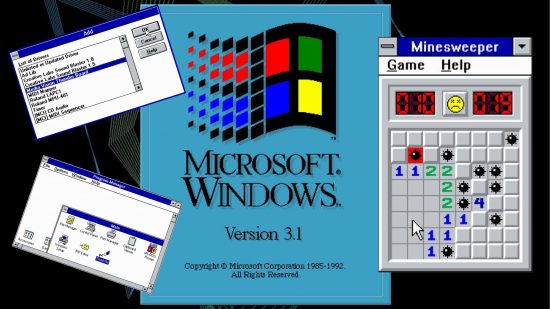

Windows 3.1 is arguably the most crucial version of Windows ever – the Windows that defined how PC computing looked just as it was beginning to take off. Before version 3.1, Windows was a successful operating system, but one that looked and felt like a GUI shell perched precariously on DOS.

With the launch of Windows 3.1 in April 1992, Windows finally looked and felt like the real deal. What’s more, it was a sales phenomenon, shipping over 3 million copies in its first six weeks on the market and 25 million within the first year. Windows was already big, but 3.1 put Windows in the lead.

How did Windows 3.1 do this? That’s not something you can nail down to any one factor. It was partly a question of stability, partly features, and partly look and feel. Believe us – Windows 3.1 looks rough by today’s slick standards, but not half as rough as what came before.

Look and feel

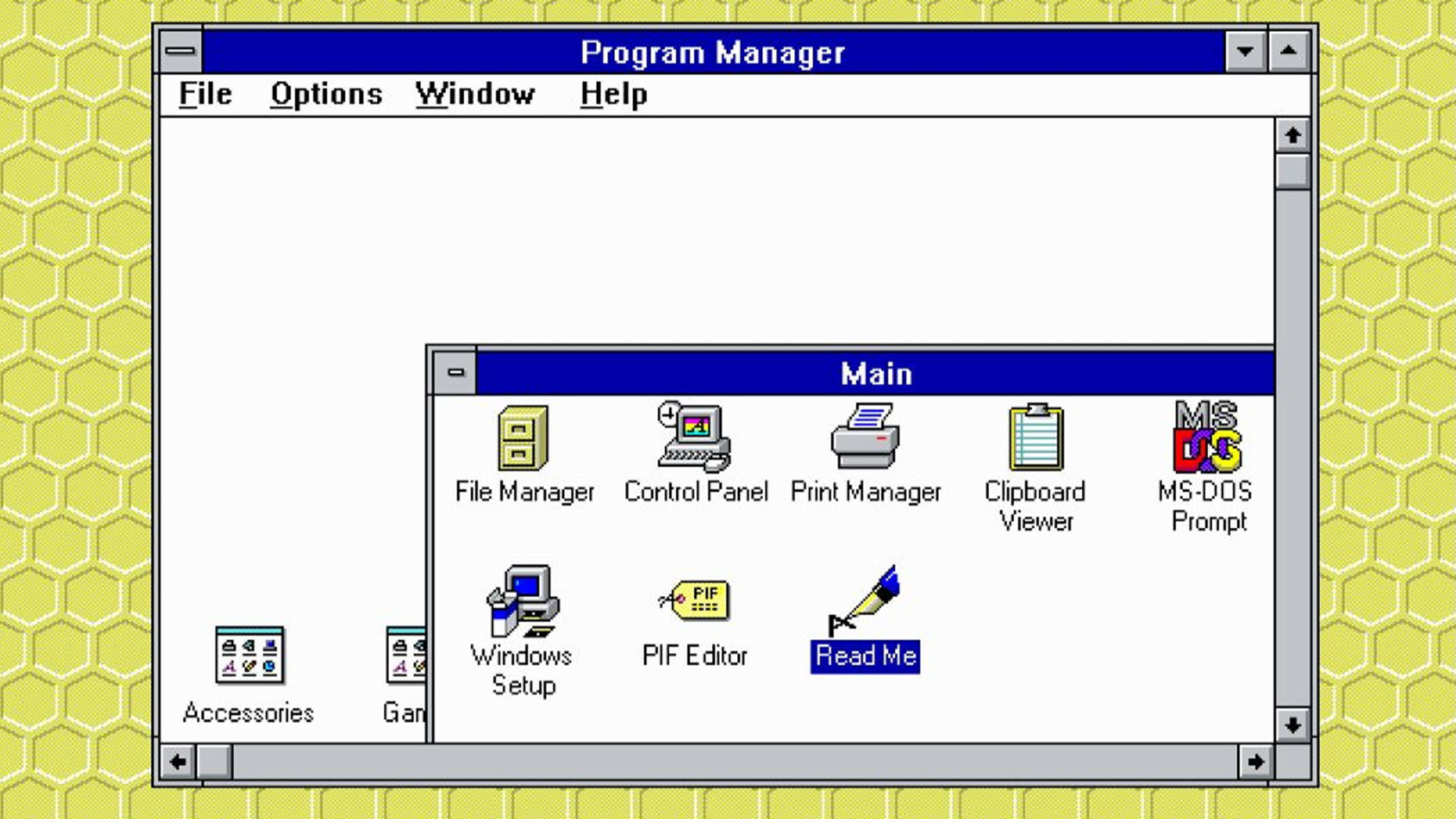

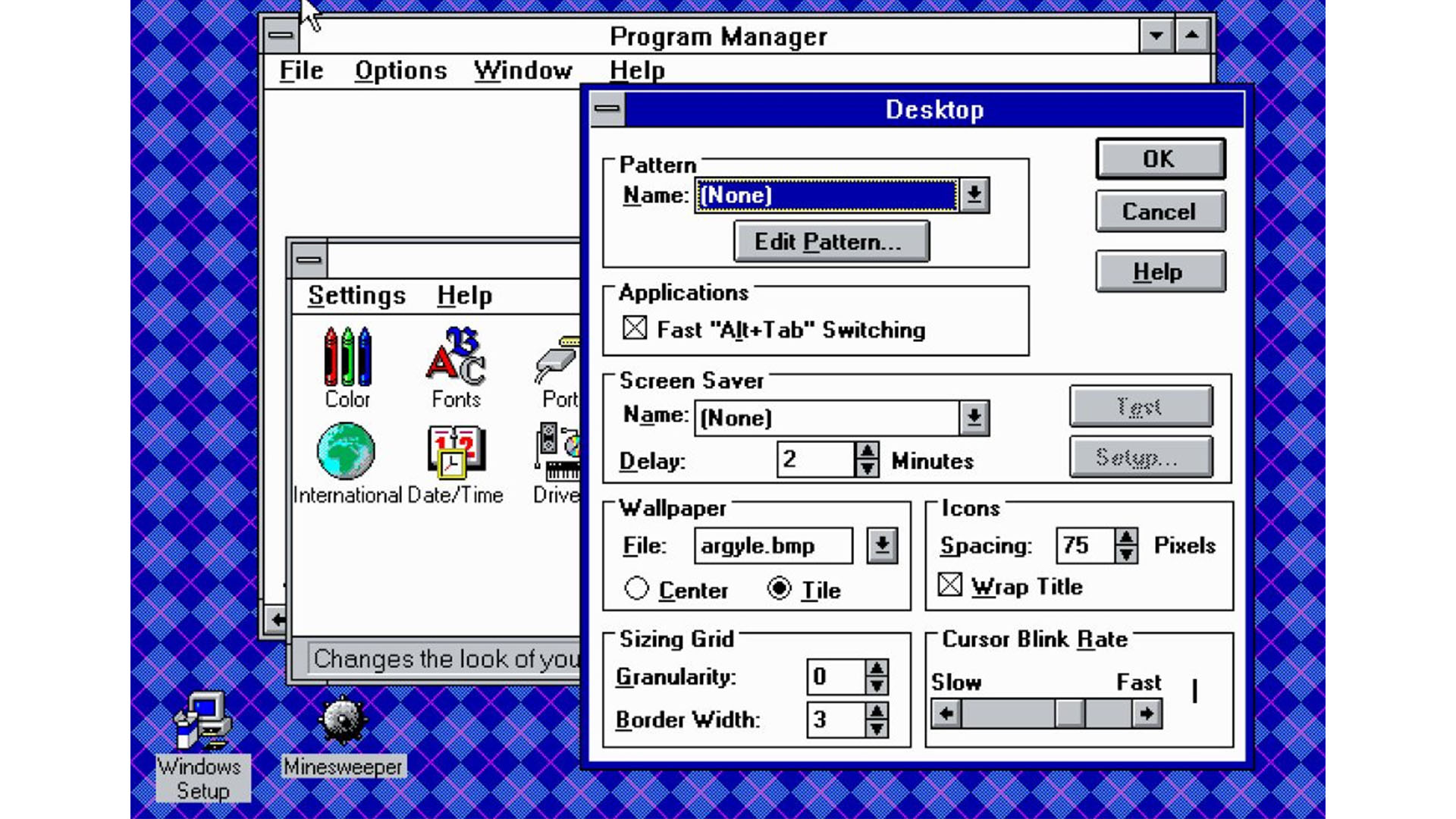

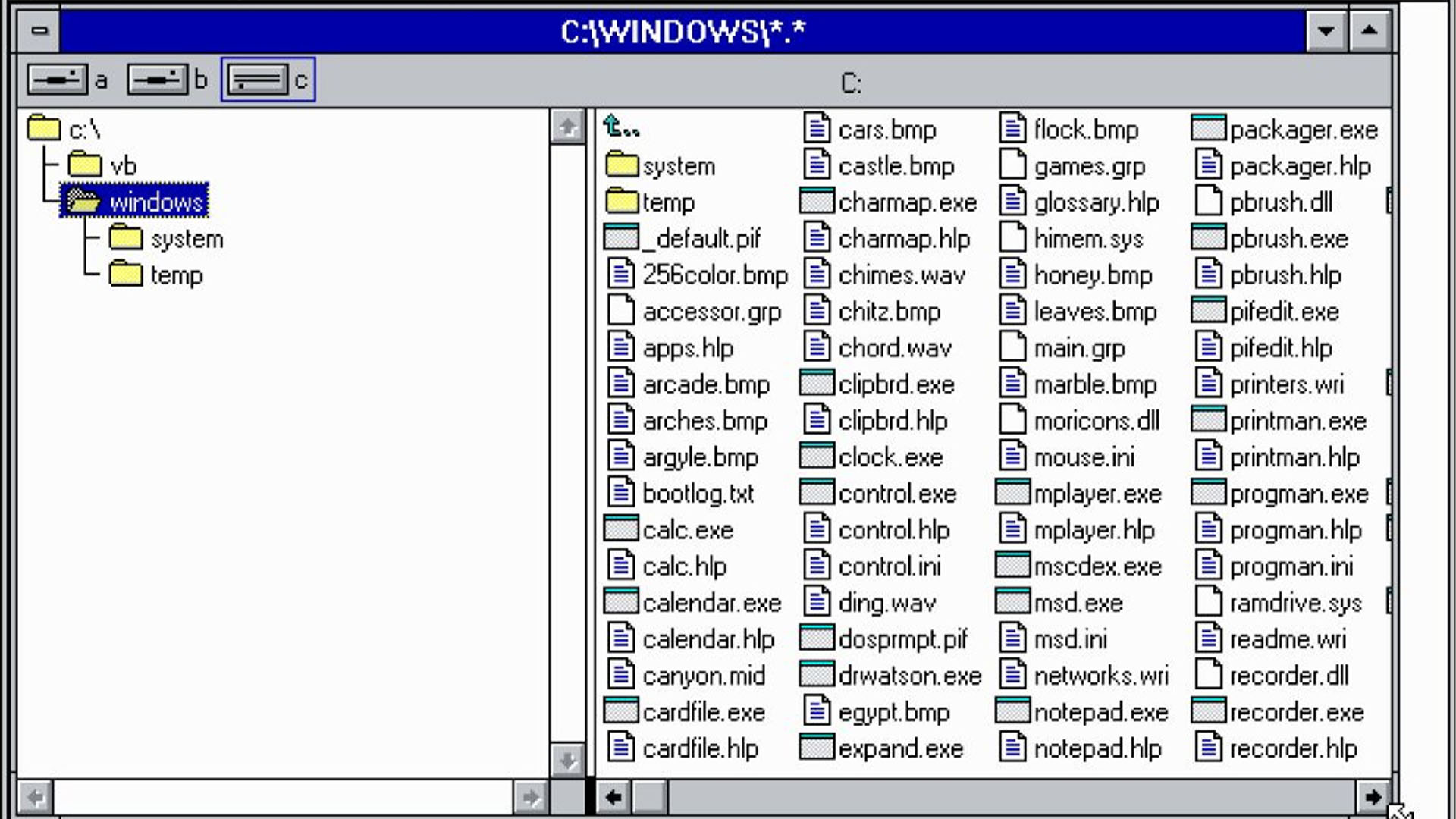

Look and feel certainly played an important part in Windows 3.1’s success. Windows 3.0 has already done some of the hard work of introducing a proper GUI, replacing the horrible, text-based MS-DOS Executive of Windows 1.x and 2.x with the new Program Manager and File Manager components.

Instead of clicking on a program or a file in a list, you could double-click on an icon to launch it. Yet Windows 3.1 went further, taking advantage of the VGA and SVGA graphics standards to introduce a revamped UI with more colorful icons.

What’s more, those icons could now do more than just get clicked on, as Windows 3.1 introduced drag and drop. You could explore your PC’s file system visually, copying files from one folder to another by clicking on the file, dragging it over and releasing the mouse button. You could drag a file onto the Print Manager icon to print it out, or onto the application’s icon in Program Manager to open it and start work.

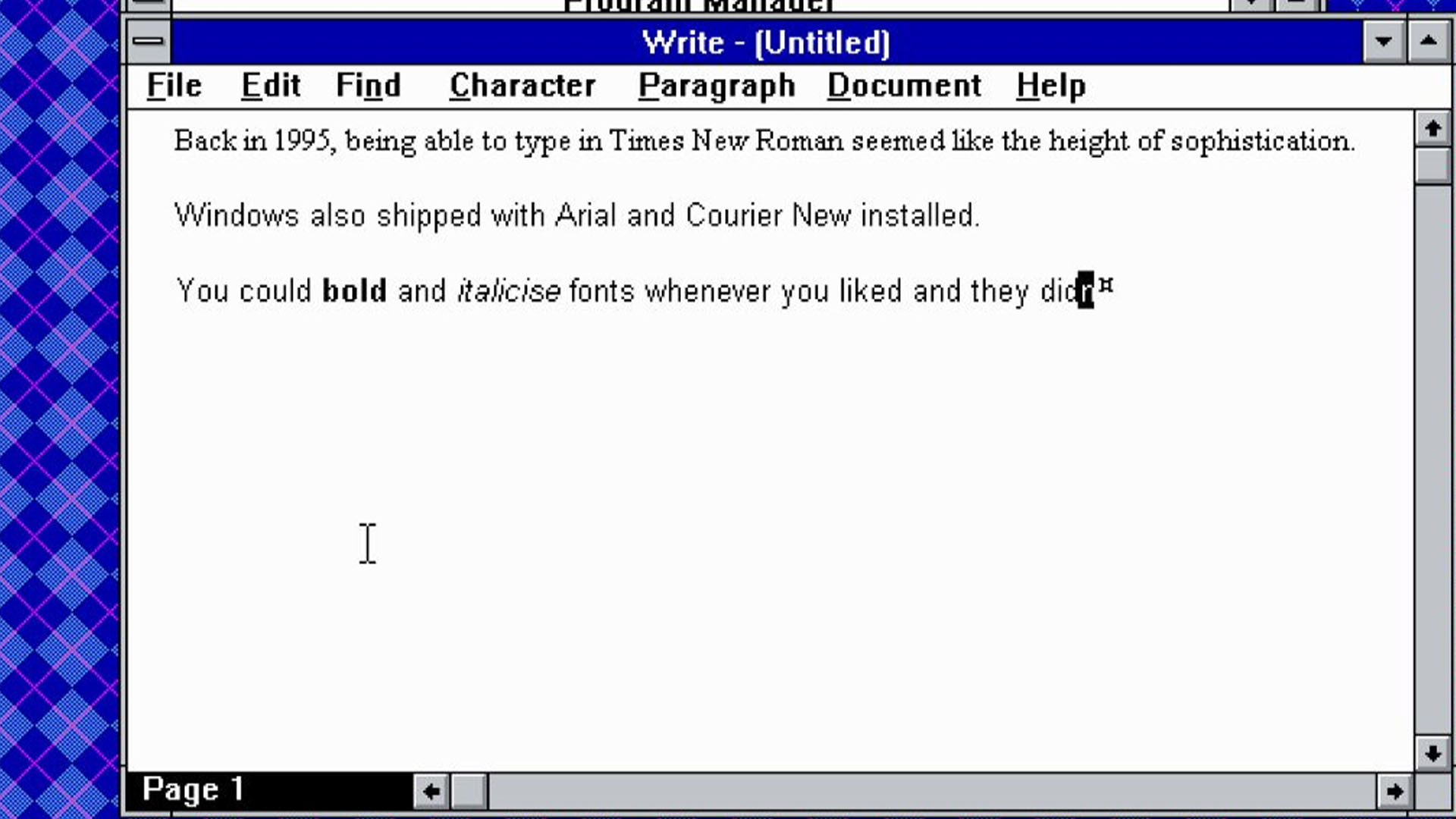

Yet perhaps the most vital enhancement over Windows 3.0 was the introduction of TrueType fonts. At this point, Windows still involved a lot of text and, up until Windows 3.1, this text didn’t look good. It was pixelated, primitive, and ugly, with no real provision to vary horizontal or vertical spacing.

While developing Windows 3.1, Microsoft put a team together to fix this problem, and that team worked with one of the two leading typesetting companies of the era, Monotype, to design a new set of core fonts. Meanwhile, Microsoft worked on the technology to render those fonts on-screen, so they could be scaled upwards and downwards, rotated and respaced, and still look pretty good.

Monotype came up with the Times New Roman, Arial, and Courier New fonts that Windows still incorporates today, while Microsoft licensed and adapted Apple’s TrueType technology, adapting the font hinting tech that made these fonts clear and legible even on a VGA resolution ( 640 x 480 ) screen. This not only made Windows look a whole lot better, but made it a viable platform for desktop publishing and design. Suddenly, the Mac had competition.

Fun and games

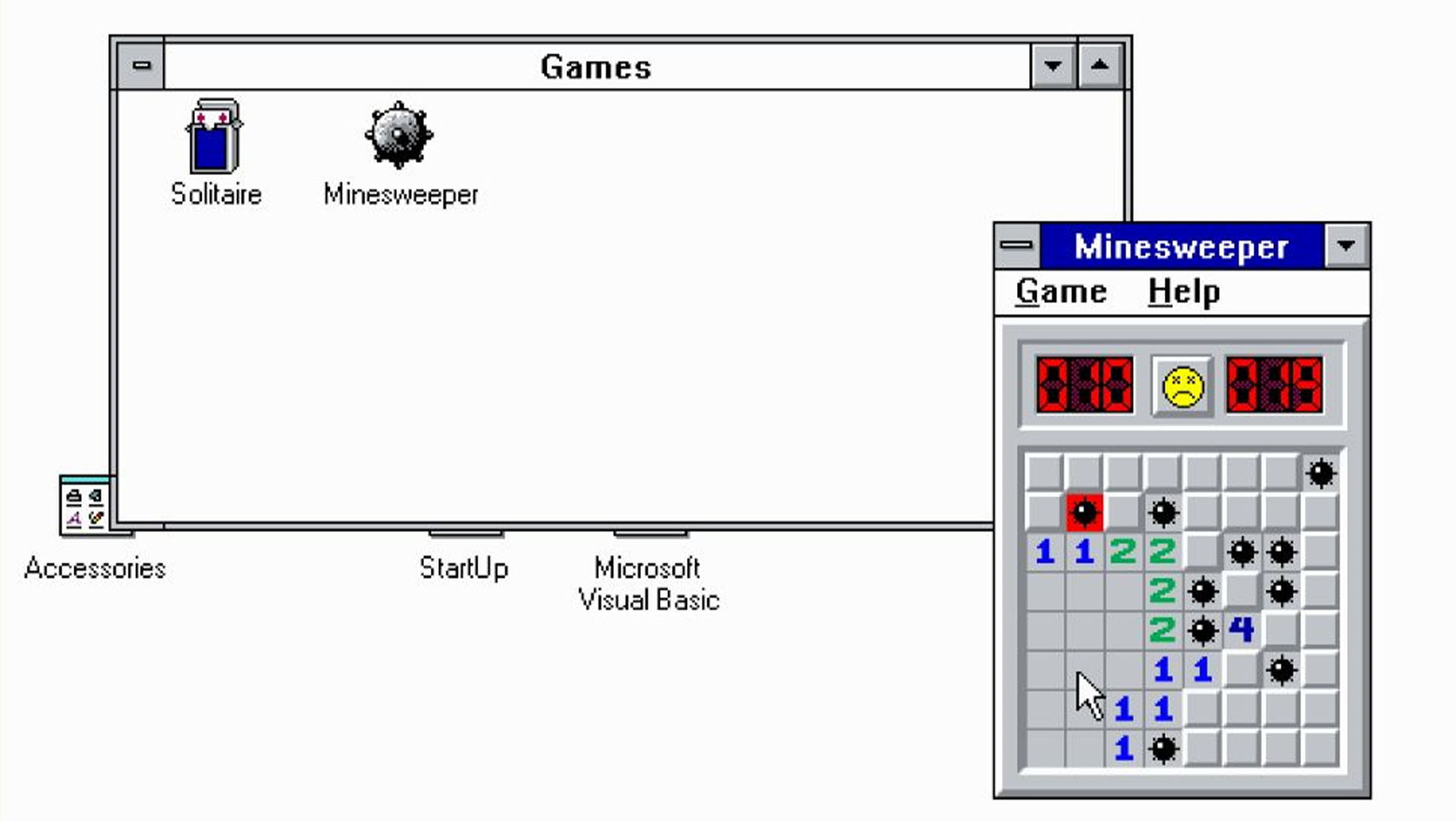

Other aspects of Windows 3.1 revealed a more playful side to Microsoft. Windows 1.0 includes one game – Reversi, while Windows 3.0 introduced Solitaire, a patience card game originally developed by a Microsoft intern, Wes Cherry, and responsible for so much lost productivity that Microsoft banned its ‘boss key’ feature, which switched from the game to a mocked-up Excel spreadsheet, before release.

Windows 3.1 added Minesweeper, the classic game of grid-based bomb discovery so addictive that, legend has it, Bill Gates had it uninstalled from his PC. Not that this stopped him or anyone else playing it. While Gates was known to sneak onto a colleague’s computer after hours to play it, the rest of the company joked that Minesweeper was the most carefully tested of all Windows 3.1’s new features.

This was also the first version of Windows to include a built-in screensaver. As with so many new features, this wasn’t all that new – screen burn-in was an issue for CRT-based VGA monitors, and After Dark’s fish and flying toasters had already appeared on Windows 3.0 and macOS.

However, Windows 3.1 made screensavers a standard component, introducing long-time favorites, such as the classic flying Windows logo, the Star Trek-style Starfield, and the psychedelic Mystify and Swirl. Seriously. After few too many shandies, they blew our primitive, PC-loving minds.

Architectural improvements

Yet the most important features that Windows 3.1 introduced were those you couldn’t see. Windows 3.0 had introduced protected memory – a way of using the protect mode of the 80286 CPU to allow Windows and Windows apps to use up to 16MB of RAM rather than just the first 640KB.

Coded by ex-physicists David Weise and Murray Sargent, this feature had been crucial, making Windows a viable alternative for Microsoft to working with IBM on what would become OS/2. Running in protected mode gave Windows programs more stability, and enabled MS-DOS applications to run under Windows and still access all the available RAM. This in turn meant that Windows spent less time crashing, which made it a lot more attractive to people trying to get some actual work done.

Windows 3.1 built on this foundation by taking the new memory management features built into the newer 386 processors and using them in a 386 Enhanced mode. Where Windows 3.0 was limited to a maximum of 16MB, Windows 3.1 upped that limit to 256MB (or, in theory, up to 4GB) and enabled programs to use virtual memory above and beyond the physical memory installed.

It also enabled most DOS programs to be run inside a Window with mouse support, and multiple DOS programs to be run simultaneously. What’s more, all these enhancements meant Windows 3.1 only worked on an Intel 80286 CPU or later. Rocking an old-school Intel 8086? Tough.

These changes improved not just Windows’ overall stability, but its multi-tasking capabilities as well. Applications mostly got the resources they needed, and a central messaging system alerted them to hand over resources as and when they were needed, although not all Windows programs behaved as well as others. A Task List enabled you to see all the currently running programs and halt any that were gumming up the system, although the more likely outcome was that they would crash Windows first.

What’s more, all of this went hand in hand with another major Windows feature. Windows already had the Dynamic Data Exchange (DDE) protocol, which allowed you to take messages and/or data from one Windows program to another. Windows 3.1 went one better with Object Linking and Embedding (OLE), which enabled you to embed an object created by one application into a document created by another, with both apps updating seamlessly when you made any changes.

Suddenly, you could create a chart in Microsoft Excel and stick it in your Microsoft Word report, then update the data in Excel and see the changes rolled out in Word. I know. It doesn’t sound that thrilling, but at the time, this rocked the computing world.

Last, but not least, Windows 3.1 gave the world the Windows registry. At the time, this central database of settings wasn’t all that well known or understood, and we never felt the need to edit it directly as we would in the Windows 95 years. Still, it showed a willingness to gather vital system information and preferences in one place, rather than in a horde of SYS, INF and INI files, as had been the Windows way until this point.

Confounding issues

Let’s not heap too much praise on Windows 3.1; it still had its fair share of issues. One was that Windows still didn’t support long filenames, so both files and directories were limited to names eight characters long, followed by a three-character suffix that told the OS what kind of file it was. This meant users became ingenious at truncating filenames, which in turn made looking through a folder full of documents or save games feel like decoding some esoteric text.

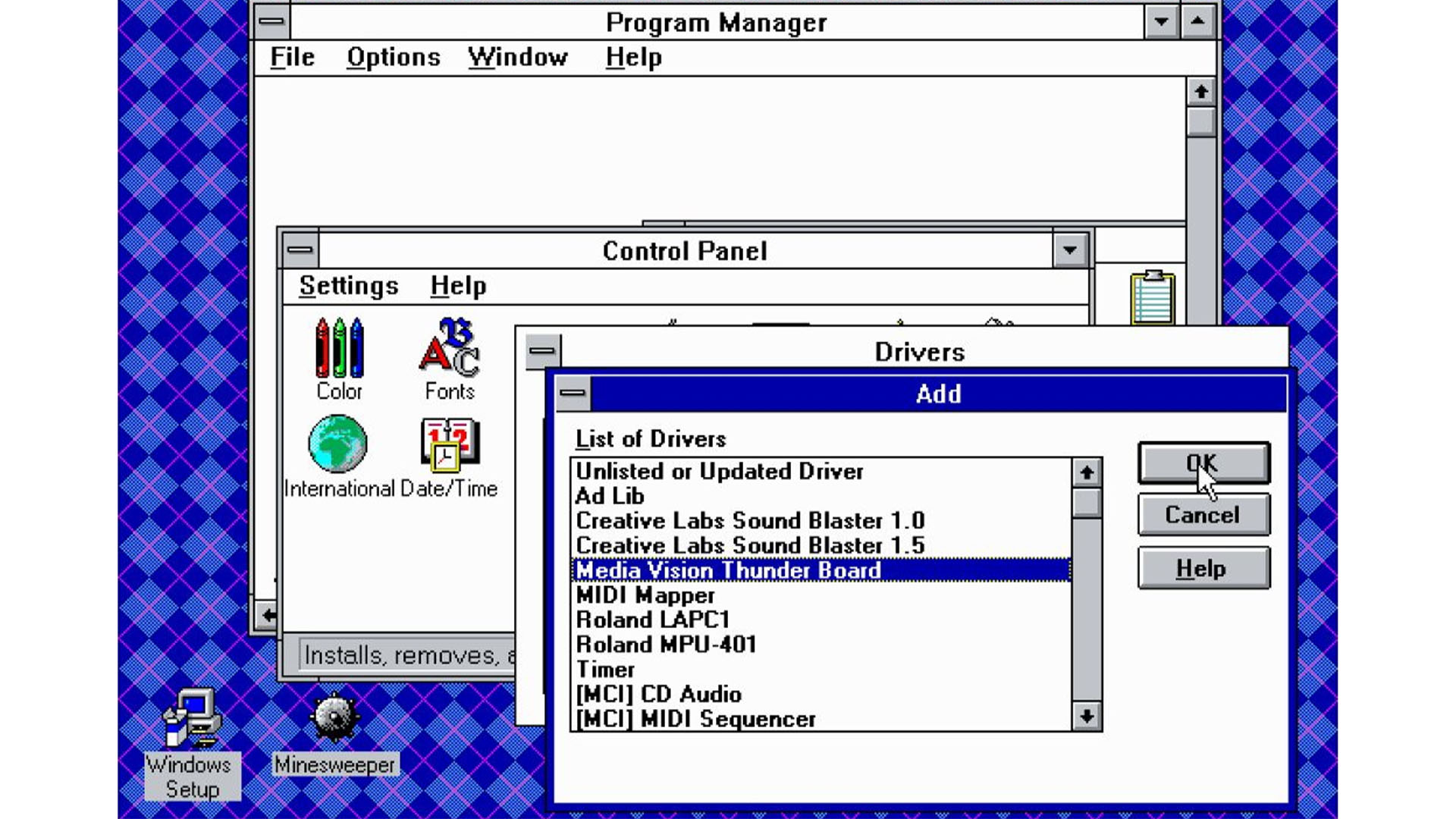

What’s more, while Windows 3.1 had support for multimedia hardware, which was just about becoming affordable and available, ease of installation wasn’t on Microsoft’s list of priorities. Restrictive hardware didn’t help – these were the days when solving hardware conflicts involved moving jumpers from pin to pin to swap Direct Memory Access channels. However, Windows 3.1 made the whole process of installing drivers for a CD-ROM drive and sound card as challenging as possible – it might take hours to get the whole setup running.

Networking wasn’t any better either, because Windows 3.1 didn’t have any built-in networking support. Instead, it piggy-backed on networking clients for the underlying MS-DOS operating system. If you hadn’t already mastered Novell Netware or Microsoft LAN Manager, you were still going to have to get to grips with them here.

Nor was the Windows shell ideal. Simply finding a program in Program Manager could be daunting, especially if you weren’t sure which folder or group held it. With screen space at a premium, you would have to constantly minimize and restore Windows while you looked. Don’t even ask about finding files in File Manager.

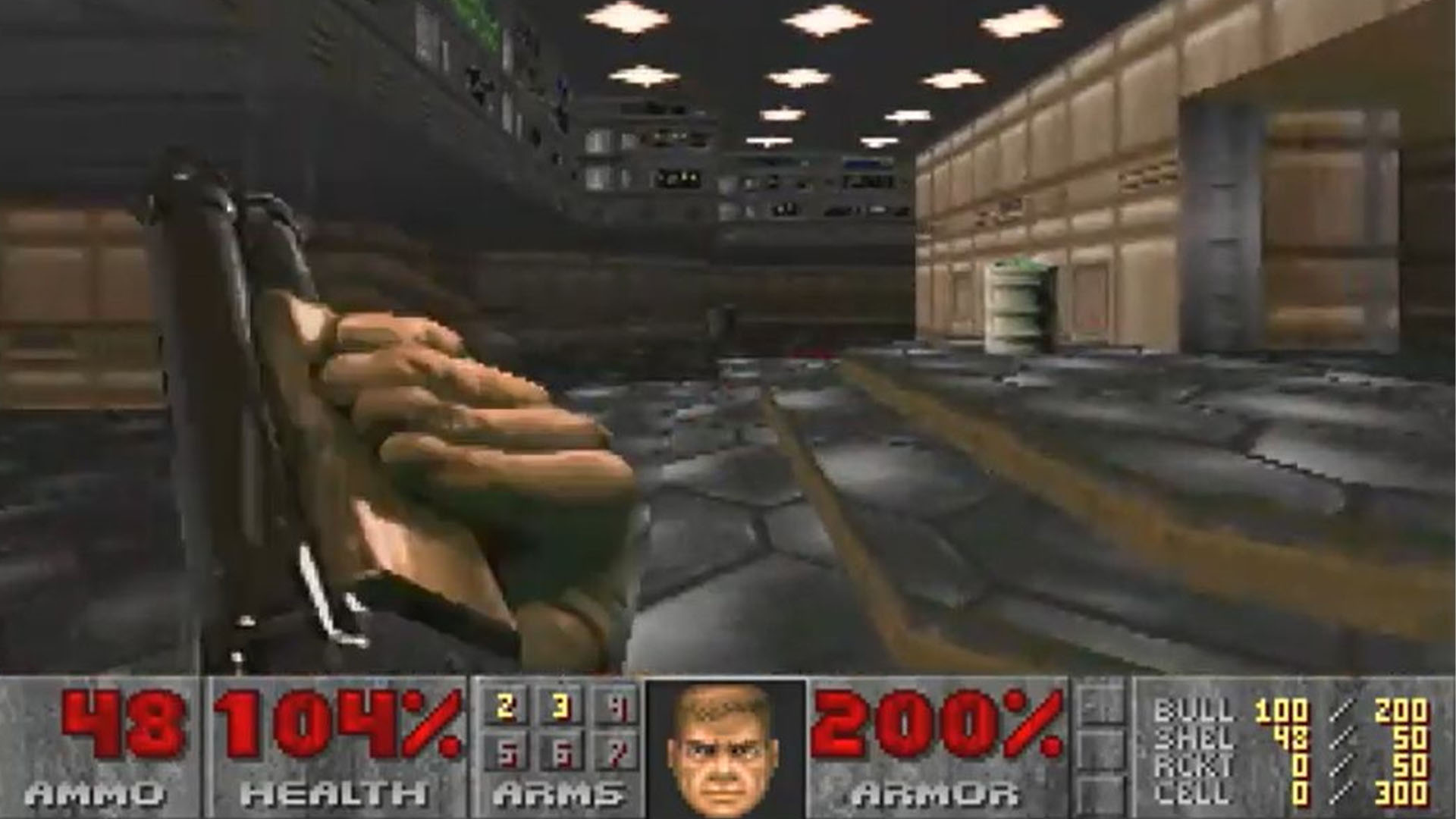

Most of all, Windows wasn’t a great platform for games. Dodgy drivers and the massive overheads involved in just running Windows itself made it much, much easier to run Wolfenstein 3D or The Secret of Monkey Island 2 in DOS, which Windows needed to run anyway and for which all Windows users had to pay.

This also meant that getting games running still required tinkering at text editor level with a range of crucial system files, to the point that most PC gamers were on intimate terms with config.sys, himem.sys and autoexec.bat. Windows 3.1 didn’t change this one bit.

With time, there was some movement. In 1994, Microsoft released a new API, WinG, which was designed to deliver faster graphics performance under Windows and encourage more developers to port their DOS games. WinG worked on a technical level, as proven by a WinG port of id Software’s Doom. Yet it didn’t work so well on the commercial level, with developers looking at the work involved and the existing DOS user base, then shrugging their shoulders until Windows 95 and DirectX came along.

Still, for all these faults, Windows 3.1 was a major leap in the right direction, paving the way not just for Windows 95, but for the switch from IBM and OS/2 towards Windows NT. Without that we might never have had the PC boom of the mid-1990s, Windows XP and everything beyond. And where would we all be without that?

Where indeed? That brings us to the end of our Windows 3.1 retrospective. We hope you’ve enjoyed reminiscing (or probably learning for the first time!) about the days of Minesweeper addiction, and the joy of having a proper icon-driven version of Windows. We might complain about Windows 11 now and then, but it’s amazing compared to the DOS-based versions of Windows we had years ago.

Bringing us back to the present day. If you’re looking to build a new Windows gaming PC, make sure you read our full guide to the best gaming CPU, which covers the best options at a range of prices. You’ll also want to check out our full guide on how to build a gaming PC, where we take you through the whole process from start to finish. For more articles about the PC’s vintage history, check out our Retro tech page.