Our Verdict

77%A detailed and even enjoyable look at a relatively understudied field, and one that largely avoids lauding or demonizing its occupants.

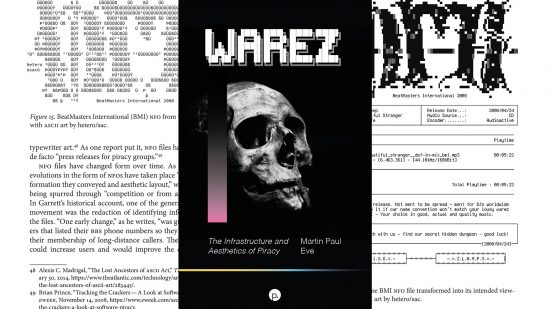

Martin Paul Eve’s Warez: The Infrastructure and Aesthetics of Piracy book proclaims itself ‘the first scholarly research book about the Warez Scene’, and it delivers its promise. This isn’t a coffee table book, and there are very few illustrations to break up the text.

Even the fifth chapter, dedicated to aesthetics, has only four images – two screenshots of a demo released in 2009, largely unrelated to the central topic, and two examples of the ASCII art commonly found at the top of NFO (info) files – one rendered using the wrong codepage, the other rendered correctly.

Compared with a book such as Crackers I: The Gold Rush, with its double-page image spreads and full-color gloss, Warez is positively spartan, despite treading much of the same ground. Both books look at groups responsible for distributing copyright material, although Eve’s focus is less on software and more on media.

Many academic publications are dry, and Eve has struck a balance with Warez that manages to avoid this pitfall while still adhering to the requirements of a scholarly tome. Impressively, it manages to take a beat or two to entertain the reader as well.

His approach to research may raise some eyebrows, however. At no point during the preparation of the book did he speak directly to anyone in the warez scene, past or present. Instead, he sought to ‘infer its operation from […] archival objects’ – in particular, archives of NFO files, messenger logs and digital magazines.

There are direct quotes to be found, leaning on interviews published by others on the same topic. There are also lifts straight from the archives in question, complete with l33tsp33k and the occasional swear word. Eve takes a detour at one point to discuss the subject of hate speech, ‘usually homophobia’, in scene publications – then later looks at the ‘translation of certain non-English characters to blocks’ for ASCII art as a form of ‘computational, linguistic colonialism’.

Eve’s biggest take, and one that’s argued persuasively, is that the warez scene – despite being entirely about the redistribution of others’ copyrighted intellectual properties without permission or recompense – is, effectively, a giant alternate reality game in which participants vie for recognition and respect among their peers, while at the same time trying to hide their illicit activities from the world.

Warez is extremely thoroughly researched, albeit primarily through digital archaeology, as the 72-page bibliography and impressively detailed appendix proves. It covers ‘topsites’ and ‘dumps’, with dozens of pages of tabulated data including site names, operator aliases, known affiliates and more.

The overall feel of the book, however, is rather scattershot. The bulk focuses on the turn of the century, from which the digital corpus used as a primary source was extracted, but the chapter on legal takedowns reaches right up to 2020 – and even discusses Bitcoin.

There are moments when Eve is clearly operating outside his field of expertise. One comes early in the book, in its four-page glossary ahead of the first proper chapter. Here, the author attempts to describe the operation of a RAID array but claims striping – rather than mirroring or parity – exists to ‘protect against the risk of catastrophic drive failure and data loss’.

Warez price

Price: Expect to pay $26 / £22

Warez review conclusion

Despite these moments, Warez is a detailed and even enjoyable look at a relatively understudied field, and one that largely avoids lauding or demonizing its occupants. Warez is available as a free download, or in print from Amazon (see above).