The technology that put PC graphics firmly on the map arrived in April 1987 as part of IBM’s PS/2 line of PCs. IBM saw the PS/2 as the answer to its biggest problems, putting Big Blue (as we all used to call it) back in control of the PC architecture and one step ahead of the clone manufacturers.

To do so, it had Intel’s latest processors, cutting-edge connection options and the fastest floppy disk storage, not to mention a revolutionary new high-bandwidth system bus. But what turned out to be the PS/2’s most important feature was its new graphics hardware – the Video Graphics Array, or VGA.

In 1987 the PC wasn’t exactly considered a graphics powerhouse. Apple’s Mac II, launched in March the same year, had a graphics card that could support up to 256 colours at 512 x 384. The Commodore Amiga could display full-screen animated graphics with up to 64 colours at 320 x 240, or 4,096 colours in still images using its legendary, flicker-tastic HAM mode.

The best the PC had to offer was the EGA (Enhanced Graphics Adapter) standard, covering resolutions of up to 640 x 350, but with only 16 simultaneous colours from a fixed palette of 64. If you wanted to create graphics or play games on your PC, you needed to really like basic colours with a strange preponderance of green and purple. Graphics enthusiasts were rendering ray-traced 3D graphics on their Amigas, albeit very slowly, but nobody sensible would even think of doing so on a PC.

VGA didn’t put the PC at the graphics cutting edge, but it did put it back in the race. The new hardware supported resolutions of up to 640 x 480 with 16 colours, or 320 x 200 with up to 256. What’s more, those 256 colours could be redefined at any time, from an 18-bit palette of 262,144 colours. With VGA, you could put a photo on the screen and it kind of looked like a photo. Artists could create 2D images with sophisticated colour and shading effects. PC games went from looking shocking to looking seriously awesome. VGA was literally a game changer.

PC graphics get the wow factor

Weirdly, VGA didn’t arrive as a new standard, or even as an add-in graphics card. On the first PS/2 PCs, it came in the form of a chip containing the display controller, along with 256KB of dedicated RAM, a pair of timing crystals and an external RAMDAC.

This already made it a much more integrated technology than the original EGA chipsets, which contained dozens of processors, and put it more in line with the integrated chips coming from third parties. What’s more, it was the higher-end option of two new graphics standards. The cheaper PS/2 models were stuck with the Multi Colour Graphics Adapter (MCGA) which had the same 256-colour mode but lacked VGA’s higher resolutions.

Like IBM’s new MCA bus architecture, MCGA didn’t last long beyond the PS/2, but VGA developed a life of its own. Beyond hardware-level support for smooth scrolling, and a barrel shifter designed to shift incoming data from the CPU to the display at seven bits at a time, it didn’t actually do much in the way of graphics acceleration.

However, it did set a new baseline standard for PC graphics, and for hardware and software support. Crucially, through its RAMDAC and 15-pin D-Sub connector, it established how the PC could convert digital instructions into a 256-colour analogue video signal, setting the stage for the 16-bit and 24-bit colour standards to come.

Instead of sending six colour signals from the graphics card to the monitor, like the older EGA chipsets, the VGA chipset and its RAMDAC sent only three signals – red, green and blue, with a potential 64 different levels for each. For VGA, this resulted in an 18-bit palette of up to 262,144 colours, 256 of which could appear simultaneously in Mode 13h. Once adopted, this same core technology gave scope for 16-bit and 24-bit colour in later graphics chips, with up to 65,536 colours or 16.7 million colours on the screen at once.

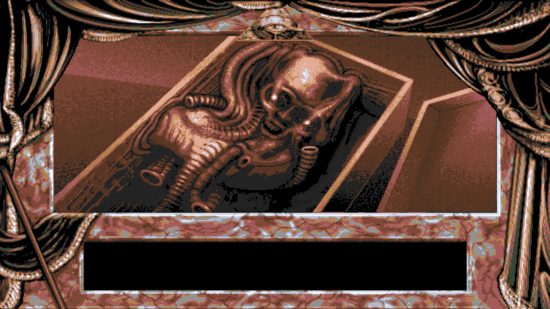

Resolution wasn’t the base level VGA spec’s strength. In fact, PC journalists of the time pondered why it was stuck at 320 x 200 in Mode 13h. However, programmers found workarounds. A handful of games, such as the legendary horror game Dark Seed, opted to work with a reduced 16-colour palette in order to use the full 640 x 480 resolution. Meanwhile, Michael Abrash, who would later work with id Software on Quake, worked out an approach that enabled programmers to use 256 colours at a slightly higher resolution of 640 x 240, which he dubbed Mode X.

Meanwhile, Windows 2.0 moved to adopt the 640 x 480 mode with 16 colours, bringing the interface closer to what we expect from a GUI today. However, many of the applications and games we think of as belonging to the VGA era stuck to Mode 13h and its 320 x 200 resolution. What’s more, with the CPU performing most of what we’d now call the GPU’s legwork, this was arguably for the best – until the Intel 486 appeared in 1989, there wasn’t any really CPU powerful enough to handle gaming at higher resolutions.

The impact of VGA

Luckily, those colours alone had a huge impact. The ZSoft Corporation’s PC Paintbrush and Electronic Arts’ Deluxe Paint II revolutionised professional graphics and computer art on the PC, thanks to 256-colour support. VGA also made CorelDRAW, launched in January 1989, a realistic alternative to the digital design packages appearing on Apple’s computers.

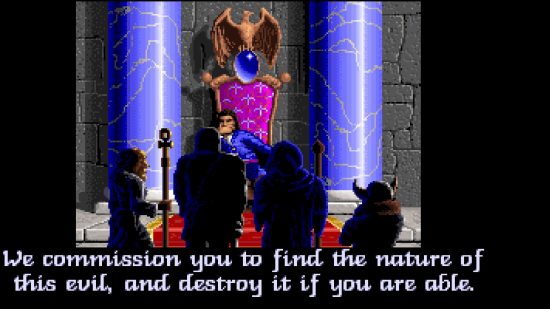

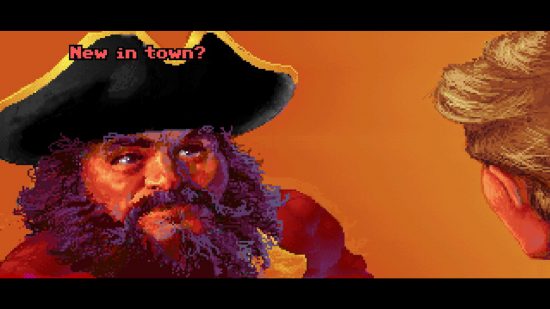

Meanwhile, for PC games, VGA was nothing short of transformative. Sure, the 64,000 pixels on your monitor looked a little chunky; however, with 256 colours, the artists working at leading developers, such as LucasArts, Sierra Online, Microprose, Electronic Arts and Origin Systems, were able to produce sprites that looked more like recognisably human (or inhuman) characters, and background scenery that could bring their game worlds to life.

Plus, while the PC couldn’t pull off the same smooth scrolling, sprite-scaling tricks as the Commodore Amiga or 8-bit consoles, its best games were developing a visual richness of their own. As the PC moved into the 386 era, it was beginning to be taken seriously as a gaming machine. Taken on its own, the first VGA chipset wouldn’t have made such an impact.

After all, you only got it to use it if you bought a pricey IBM PS/2 machine. Instead, it really only gained momentum once it began to appear in add-in cards. IBM was first out of the gate with its PS/2 Display Adapter, a card that gave any reasonably modern IBM-compatible PC with ISA slots a VGA chipset for the princely sum of $599 US (about £420 inc VAT then and £1,200 inc VAT in today’s money).

Yet by this point, the older EGA standard had spawned a growing industry of third-party manufacturers, adept at mimicking or reverse-engineering IBM’s technology and spawning their own versions. What’s more, these guys didn’t stop at simply replicating IBM’s latest standards; they wanted to add a little extra sauce to their cards by actively enhancing them.

As a result, October 1987 saw the launch of the first VGA-compatible third-party graphics card, the STB VGA Extra. It did everything VGA did, albeit with a few foibles here and there, with some optimisations that made it slightly faster.

By mid-1988 to 1989, the likes of Tseng Labs, Cirrus Logic, Chips and Technologies and ATi were entering the fray, and not only were they driving prices down to $339 US, but they were also adding new capabilities. These enhanced VGA cards added features to accelerate video, or increased the RAM to 512KB, and tinkered with the BIOS to cover more advanced resolutions, such as 800 x 600 in 16 colours or 640 x 480 with 256 colours.

This in turn put pressure on the system bus. The original VGA controllers were so undemanding that they couldn’t exhaust the miserable bandwidth of the 8-bit ISA bus, but as these new chipsets emerged, they required more bandwidth and a spot on the wider 16-bit ISA bus.

As time went on and Intel’s CPUs grew faster, demands would grow accordingly, resulting in the development of the Extended ISA (EISA) bus and VESA Local Bus. However, this complicated the situation further, with the fastest enhanced VGA cards, based on Tseng Labs or Cirrus Logic tech, performing best in 16-bit versions running on the 16-bit ISA bus, although this wasn’t always the case with every chipset.

By 1989, NEC would lead the early graphics chipset manufacturers in the creation of the Video Electronics Standards Association and the Super VGA BIOS, opening up support for higher resolutions and colour depths across the PC industry. Windows acceleration became the new battleground and video acceleration became the next cutting-edge technology.

Yet all these new cards and advanced feature sets still had the VGA standard at their core. VGA became the base requirement for new PCs running later versions of Windows or IBM’s OS/2. In many respects, IBM had built the foundation of PC graphics for the next ten to 15 years. In fact, you could argue that VGA is still the foundation.

If so, it probably wasn’t a whole lot of comfort to IBM. While VGA was the last graphics standard IBM managed to establish, it wasn’t for the want of trying. Even as it launched VGA, it was preparing its 8514 graphics adaptor, with fixed functions to accelerate common 2D drawing processes, such as drawing lines or filling shapes with colour. In 1990, it hoped to supersede VGA with its new 1,024 x 768, 256-colour standard, XGA.

Both these new standards floundered because they were designed to run on IBM’s MCA bus, while IBM’s clone-making rivals focused on getting the most out of the existing 16-bit ISA bus, before working on the proposed EISA replacement. The result? Super VGA became the new de facto standard, while IBM lost its domination of the PC industry. Bad news for Big Blue, but good news for those of us who enjoyed the more cost-conscious, game-focused machines in the years that followed.